(s.m.) On the calendar released by the Vatican at the end of March for the Paschal celebrations this year, the Mass “in coena Domini” on the evening of Holy Thursday was missing entirely.

(s.m.) On the calendar released by the Vatican at the end of March for the Paschal celebrations this year, the Mass “in coena Domini” on the evening of Holy Thursday was missing entirely.

Since Jorge Mario Bergoglio has been pope, it has always happened like this. Only at the last moment was it made known where he would celebrate, usually at a prison. And the news concerned not so much the Mass, but the washing of the feet that he would do for twelve prisoners or immigrants, men and women, Christians, Muslims, with or without faith.

The homilies too, given in these circumstances by Pope Francis, were wholly in keeping with the absolute priority given to the washing of the feet. They were of few words, improvised, almost always and only reduced to an exhortation to forgiveness and fraternal service.

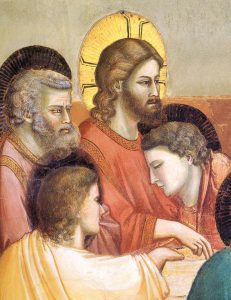

As for the Mass, there was usually not even a mention. And yet that of Holy Thursday is a cornerstone of the Christian liturgy, the memorial of the Last Supper of Jesus with the apostles (in the illustration, a detail frescoed by Giotto in 1303), the first of all the Masses of yesterday, today, and tomorrow.

This year too, with Francis in precarious health conditions, general expectations were concentrated on who in his place would perform the washing of the feet, and where – with a substitution that in the end was dropped – and above all on the possible, fleeting appearance on the scene of the pope himself, perhaps with a visit to the nearby Roman prison of Regina Coeli.

But why not instead bring back to light what the metamorphosis of Holy Thursday carried out by the current pontiff has concealed? Why not return to the authentic heart of the Mass “in coena Domini”?

The following is the homily given at the Mass of Holy Thursday in 2008 by Pope Benedict XVI, who always celebrated it at the cathedral of St. John Lateran.

The homily is inspired by the page of the Gospel of John that is read at this Mass, where instead of the account of the Last Supper there is precisely that of Jesus washing the feet of his apostles. But what Pope Benedict draws from this is of no comparison to the superficiality of the spectacle in vogue for years.

That homiletics was a high point of Joseph Ratzinger’s pontificate is a judgment shared by many. And Settimo Cielo has already explained why, in the introduction to a book that in 2008, for the first time, collected a year of liturgical preaching by that pope.

This homily is shining proof of that. Happy reading, and Happy Easter!

*

Homily of the Mass “in coena Domini” of March 20, 2008

by Benedict XVI

Dear Brothers and Sisters, St John begins his account of how Jesus washed his disciples’ feet with an especially solemn, almost liturgical language. “Before the feast of the Passover, when Jesus knew that his hour had come to depart out of this world to the Father, having loved his own who were in the world, he loved them to the end” (Jn 13:1).

Jesus’ “hour”, to which all his work had been directed since the outset, had come. John used two words to describe what constitutes the content of this hour: passage (metabainein, metabasis) and agape — love. The two words are mutually explanatory; they both describe the Pasch of Jesus: the Cross and the Resurrection, the Crucifixion as an uplifting, a “passage” to God’s glory, a “passing” from the world to the Father. It is not as though after paying the world a brief visit, Jesus now simply departs and returns to the Father. The passage is a transformation. He brings with him his flesh, his being as a man. On the Cross, in giving himself, he is as it were fused and transformed into a new way of being, in which he is now always with the Father and contemporaneously with humankind. He transforms the Cross, the act of killing, into an act of giving, of love to the end.

With this expression “to the end”, John anticipates Jesus’ last words on the Cross: everything has been accomplished, “It is finished” (Jn 19:30). Through Jesus’ love the Cross becomes metabasis, a transformation from being human into being a sharer in God’s glory. He involves us all in this transformation, drawing us into the transforming power of his love to the point that, in our being with him, our life becomes a “passage”, a transformation. Thus, we receive redemption, becoming sharers in eternal love, a condition for which we strive throughout our life.

This essential process of Jesus’ hour is portrayed in the washing of the feet in a sort of prophetic and symbolic act.

In it, Jesus highlights with a concrete gesture precisely what the great Christological hymn in the Letter to the Philippians describes as the content of Christ’s mystery. Jesus lays down the clothes of his glory, he wraps around his waist the towel of humanity and makes himself a servant. He washes the disciples’ dirty feet and thus gives them access to the divine banquet to which he invites them.

The devotional and external purifications purify man ritually but leave him as he is replaced by a new bathing: Jesus purifies us through his Word and his Love, through the gift of himself. “You are already made clean by the word which I have spoken to you”, he was to say to his disciples in the discourse on the vine (Jn 15:3).

Over and over again he washes us with his Word. Yes, if we accept Jesus’ words in an attitude of meditation, prayer and faith, they develop in us their purifying power. Day after today we are as it were covered by many forms of dirt, empty words, prejudices, reduced and altered wisdom; a multi-facetted semi-falsity or falsity constantly infiltrates deep within us. All this clouds and contaminates our souls, threatens us with an incapacity for truth and the good. If we receive Jesus’ words with an attentive heart they prove to be truly cleansing, purifications of the soul, of the inner man.

The Gospel of the washing of the feet invites us to this, to allow ourselves to be washed anew by this pure water, to allow ourselves to be made capable of convivial communion with God and with our brothers and sisters. However, when Jesus was pierced by the soldier’s spear, it was not only water that flowed from his side but also blood (Jn 19:34; cf. 1 Jn 5:6–8). Jesus has not only spoken; he has not left us only words. He gives us himself. He washes us with the sacred power of his Blood, that is, with his gift of himself “to the end”, to the Cross. His word is more than mere speech; it is flesh and blood “for the life of the world” (Jn 6:51).

In the holy sacraments, the Lord kneels ever anew at our feet and purifies us. Let us pray to him that we may be ever more profoundly penetrated by the sacred cleansing of his love and thereby truly purified!

If we listen attentively to the Gospel, we can discern two different dimensions in the event of the washing of the feet. The cleansing that Jesus offers his disciples is first and foremost simply his action — the gift of purity, of the “capacity for God” that is offered to them. But the gift then becomes a model, the duty to do the same for one another.

The Fathers have described these two aspects of the washing of the feet with the words sacramentum and exemplum. Sacramentum in this context does not mean one of the seven sacraments but the mystery of Christ in its entirety, from the Incarnation to the Cross and the Resurrection: all of this becomes the healing and sanctifying power, the transforming force for men and women, it becomes our metabasis, our transformation into a new form of being, into openness for God and communion with him.

But this new being which, without our merit, he simply gives to us must then be transformed within us into the dynamic of a new life. The gift and example overall, which we find in the passage on the washing of the feet, is a characteristic of the nature of Christianity in general. Christianity is not a type of moralism, simply a system of ethics. It does not originate in our action, our moral capacity. Christianity is first and foremost a gift: God gives himself to us — he does not give something, but himself. And this does not only happen at the beginning, at the moment of our conversion. He constantly remains the One who gives. He continually offers us his gifts. He always precedes us. This is why the central act of Christian being is the Eucharist: gratitude for having been gratified, joy for the new life that he gives us.

Yet with this, we do not remain passive recipients of divine goodness. God gratifies us as personal, living partners. Love given is the dynamic of “loving together”, it wants to be new life in us starting from God. Thus, we understand the words which, at the end of the washing of the feet, Jesus addresses to his disciples and to us all: “A new commandment I give to you, that you love one another; even as I have loved you, that you also love one another” (Jn 13:34). The “new commandment” does not consist in a new and difficult norm that did not exist until then. The new thing is the gift that introduces us into Christ’s mentality. The new commandment consists in loving together with him who first loved us.

So too must we understand the Sermon on the Mount. This does not mean that at that time Jesus gave new precepts, which represented the demands of a humanism more sublime than that before. The Sermon on the Mount is a journey of training in identifying with the sentiments of Christ (cf. Phil 2:5), a journey of interior purification that leads us to living together with him. The new thing is the gift that ushers us into the mentality of Christ. If we consider this, we perceive how far our lives often are from this newness of the New Testament and how little we give humanity the example of loving in communion with his love. Thus, we remain indebted to the proof of credibility of the Christian truth which is revealed in love. For this very reason we want to pray to the Lord increasingly to make us, through his purification, mature persons of the new commandment.

In the Gospel of the washing of the feet, Jesus’ conversation with Peter presents to us yet another detail of the praxis of Christian life to which we would like finally to turn our attention.

At first, Peter did not want to let the Lord wash his feet: this reversal of order, that is, that the master — Jesus — should wash feet, that the master should carry out the slave’s service, contrasted starkly with his reverential respect for Jesus, with his concept of the relationship between the teacher and the disciple. “You shall never wash my feet”, he said to Jesus with his usual impetuosity (Jn 13:8). It is the same mentality that, after the profession of faith in Jesus, Son of God, in Caesarea Philippi, had driven him to oppose him when he had foretold his condemnation and the cross: “This shall never happen to you!”, Peter had declared categorically (Mt 16:22). His concept of the Messiah involved an image of majesty, of divine grandeur. He had to learn repeatedly that God’s greatness is different from our idea of greatness; that it consists precisely in stooping low, in the humility of service, in the radicalism of love even to total self-emptying. And we too must learn it anew because we systematically desire a God of success and not of the Passion; because we are unable to realize that the Pastor comes as a Lamb that gives itself and thus leads us to the right pasture.

When the Lord tells Peter that without the washing of the feet he would not be able to have any part in him, Peter immediately asks impetuously that his head and hands be washed. This is followed by Jesus’ mysterious saying: “He who has bathed does not need to wash, except for his feet” (Jn 13:10). Jesus was alluding to a cleansing with which the disciples had already complied; for their participation in the banquet, only the washing of their feet was now required. But of course this conceals a more profound meaning. What was Jesus alluding to? We do not know for certain. In any case, let us bear in mind that the washing of the feet, in accordance with the meaning of the whole chapter, does not point to any single specific sacrament but the sacramentum Christi in its entirety — his service of salvation, his descent even to the Cross, his love to the end that purifies us and makes us capable of God.

Yet here, with the distinction between bathing and the washing of the feet, an allusion to life in the community of the disciples also becomes perceptible, an allusion to the life of the Church – an allusion that John may deliberately mean to transmit to the communities of his time. It then seems clear that the bathing that purifies us once and for all and must not be repeated is Baptism — being immersed in the death and Resurrection of Christ, a fact that profoundly changes our life, giving us as it were a new identity that lasts, if we do not reject it as Judas did.

However, even in the permanence of this new identity, given by Baptism, for convivial communion with Jesus we need the “washing of the feet”. What does this involve? It seems to me that the First Letter of St John gives us the key to understanding it. In it we read: “If we say we have no sin, we deceive ourselves, and the truth is not in us. If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just, and will forgive our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness” (1 Jn 1:8ff.). We are in need of the “washing of the feet”, the cleansing of our daily sins, and for this reason we need to confess our sins.

Just how this took place in the Johannine communities we do not know. But the direction indicated by Jesus’ word to Peter is obvious: to be able to participate in the convivial community with Jesus Christ we must be sincere. We have to recognize that we sin, even in our new identity as baptized persons. We need confession in the form it has taken in the Sacrament of Reconciliation. In it the Lord washes our dirty feet ever anew and we can be seated at table with him.

But in this way the word with which the Lord extends the sacramentum, making it the exemplum, a gift, a service for one’s brother, also acquires new meaning: “If I then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet” (Jn 13:14). We must wash one another’s feet in the mutual daily service of love. But we must also wash one another’s feet in the sense that we must forgive one another ever anew. The debt for which the Lord has pardoned us is always infinitely greater than all the debts that others can owe us (cf. Mt 18:21–35). Holy Thursday exhorts us to this: not to allow resentment toward others to become a poison in the depths of the soul. It urges us to purify our memory constantly, forgiving one another whole-heartedly, washing one another’s feet, to be able to go to God’s banquet together.

Holy Thursday is a day of gratitude and joy for the great gift of love to the end that the Lord has made to us. Let us pray to the Lord at this hour, so that gratitude and joy may become in us the power to love together with his love. Amen.

© Copyright 2008 — Libreria Editrice Vaticana

————

Sandro Magister is past “vaticanista” of the Italian weekly L’Espresso.

The latest articles in English of his blog Settimo Cielo are on this page.

But the full archive of Settimo Cielo in English, from 2017 to today, is accessible.

As is the complete index of the blog www.chiesa, which preceded it.