Who knows if Pope Francis, who is the bishop of Rome and primate of the Italian Church, has cast an eye on the latest survey by the Pew Research Center in Washington, which in none other than Italy registers an unprecedented collapse in membership in the Catholic Church, a collapse that at this time is stronger than in any other country in the world.

Who knows if Pope Francis, who is the bishop of Rome and primate of the Italian Church, has cast an eye on the latest survey by the Pew Research Center in Washington, which in none other than Italy registers an unprecedented collapse in membership in the Catholic Church, a collapse that at this time is stronger than in any other country in the world.

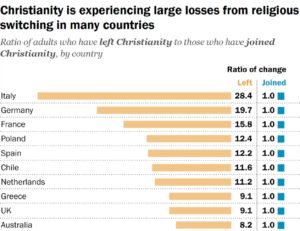

The graph to the side here provides a measurement of this. For every single person in Italy who joins the Catholic Church, more than 28 leave it. With the widest gap among the 36 countries surveyed.

The abandonment brought into focus by the graph is of those who were raised in the Catholic Church but now say they don’t belong to it anymore, having embraced another religion or, much more frequently, having renounced any religious affiliation.

Likewise out of balance, in Italy, are the flows into and out of the area of irreligion. For every Italian who leaves this area, embracing a faith, here too there more than 28 who enter it.

This abandonment of membership in the Church is massive especially among young people. Forty-four percent of Italians between 18 and 34 say they have abandoned the Catholic faith of their childhood and today do not belong to any religion (except for isolated cases of switching to another faith), as against the 16 percent of adults between 35 and 49 and 17 percent of those aged 50 and over.

The level of education also carries weight. Among Italians with a higher level of education, 33 percent say they have left the Church and no longer identify with any religion, as against the 21 percent of those less educated.

And so does sex. Among men, 28 percent say they have left the Church, while among women the figure is 19 percent.

From a cross-comparison of the 36 countries surveyed by the Pew Research Center, Christianity emerges as the religion with the highest dropout rates, followed by Buddhism, which for example in Japan has been left by 23 percent and in South Korea by 13 percent of respondents, who now identify themselves as having no religion.

But South Korea is also one of the rare cases of movement in the opposite direction. There, nine percent of those interviewed say they were raised without religious affiliation but now belong to a religion, which for the majority of them is Christianity. Today, 33 percent of South Koreans identify themselves as Christians.

The erosion of membership in the Catholic Church with the consequent increase in irreligion is a phenomenon common to a large number of countries. Some of these, particularly in north-central Europe, have already been experiencing this exodus for many years, and so today register dropout rates lower than those in Italy, where instead the phenomenon is more recent and is now reaching its highest peaks.

In Italy, the unknown about the future of this evolution largely has to do with what will happen in the vast “gray area” of those who seldom or never attend Church services and yet continue to declare themselves as belonging to the Catholic religion.

The most in-depth and up-to-date exploration of this “gray area” is in a November 2024 study conducted by CENSIS, an authoritative Italian institute of sociological research, and by the association “Essere Qui,” created a couple of years ago with the conviction that “Catholic culture still has much to offer to human, social, and economic development” in Italy and Europe, its president being the eminent sociologist Giuseppe De Rita, 92, an unforgettable protagonist of post-conciliar Catholicism, and among its prominent members the former European Commission president Romano Prodi and the founder of the Community of Sant’Egidio, Andrea Riccardi.

This study puts at 71.1 percent of the adult population in Italy the proportion of those who continue to call themselves “Catholic.”

But more in detail, only 15.3 percent of Italians declare themselves to be practicing Catholics, while the others either say they rarely attend Church functions, 34.9 percent, or define themselves as “non-practicing Catholics,” 20.9 percent.

It is this overall 55.8 percent of Italians that constitute the “gray area.” More than half of them do not identify with the institutional Church and say they do not go to church because it is enough to “live the faith inwardly,” but they all agree in considering Catholicism an integral part of the national identity and culture.

Belief in life after death is still held by 58 percent of Italians, and most of these believe that it will be a different life for those who have behaved well or badly. But in the present life, the authors of the study write, “the sense of sin is not particularly felt, in part because in the last fifty years the Catholic culture has been strongly ‘pardonist’,” and the sense of sin has been replaced with a more generic and individualistic sense of guilt.

“The ‘gray area’ in today’s Church,” the authors of the study further write, “is therefore the result of the reigning individualism, of course, but also of a Church that is only horizontal and struggles to point to a ‘beyond’.”

The risk – they add – is that even this “gray area,” left to itself, “may evaporate in a short time.” In the age group between 18 and 34, those who call themselves Catholic have already dropped to 58.3 percent, from the general average of 71.1 percent.

But it could also prove illusory for the Italian Church to “try to bring part of the flock back into the fold simply by harnessing the sense of belonging and a latent nostalgia for the sacred.”

More effective would be “to stay within the ‘gray area’ to harness that same sense of belonging and nostalgia, not in order to initiate a journey of return, but rather to enliven and illuminate the ‘gray area’ wherever it is found, to accompany the flock toward a ‘beyond’ that it no longer knows how to find but has not forgotten.”

This optimistic reading of the current condition of Catholicism in Italy echoed on Saturday, March 29, beneath the vaults of the cathedral of Rome, the basilica of St. John Lateran, at a meeting convened precisely to comment on the study by CENSIS and “Essere Qui”.

Acting as its spokesmen were Giuseppe De Rita himself with his son Giulio, the Jesuit Antonio Spadaro, very close to Pope Francis, and Sant’Egidio head Riccardi, who in concluding warned against aiming for a “creative minority,” in his judgment only consolatory, when instead “we need a Church of the people.”

For De Rita as well one must not be afraid of the “gray area,” but rely on subjectivity as the common element, even spiritual, among people who do not frequent sacred places but make the sign of the cross before a soccer game and still think about the afterlife in their own way.

Subjectivism must be considered not an enemy, De Rita further said, but the field to cultivate, in order to proceed together “onward and upward,” as Pierre Teilhard de Chardin said, that is, inseparably combining “evangelization and human promotion” and letting “the spirit work.”

“The work of the spirit” was precisely the title of the meeting at St. John Lateran. Where the “spirit” was both the rational, human “logos” and the divine “Word” that the Church has the mandate to preach, as brought to light by another of the speakers, the non-believing philosopher Massimo Cacciari.

Yet for Cacciari the Church must not passively give in to today’s “anthropological catastrophe,” but must once again present itself as “sign of contradiction,” even together with those who do not believe but want to fully build up again the dissolved “homo politicus.”

And it was precisely the need for a Church as “sign of contradiction” that was the focus of the talk – in clear countermelody to those of De Rita, Riccardi, and Spadaro – by the priest of Rome Fabio Rosini, a biblicist and professor of the communication of the faith at the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross.

For Rosini, the “gray area” is the sign of a growing irrelevance of the Church in society, if not of a real and proper “ecclesial suicide,” made of subordination to the powers of this world and of the reduction of the Christian proclamation to a sad moral preceptualism.

To get results “in complete countertendency to the statistics of the study,” Rosini said, “there is no need to make the slightest curtailing of the sign of contradiction that is the Gospel.” And he cited a memorable talk by Joseph Ratzinger from 1969:

“The future of the Church can and will come only from the strength of those who have deep roots and live from the pure fullness of their faith. It will not come from those who only make prescriptions. It will not come from those who only adapt to the moment at hand. […] From today’s crisis, this time as well there will emerge tomorrow a Church that has lost much. It will become small and will largely have to start over again. It will no longer be able to fill many of the buildings constructed during the economic boom. Along with membership numbers it will lose many of its privileges in society. It will present itself much more strongly than before as a voluntary community, accessible only via decision. […] The future of the Church will this time too, as always, be shaped anew by the saints: by men, that is, who take note of more than the latest modern clichés.”

In short, the “gray area” of Catholicism in Italy is not a reality to be acquiesced to, Rosini concluded, but “a providential opportunity to be a prophetic Church.” A bold undertaking, because “the Church is the place of the sublime” and “the beautiful and the easy have trouble getting along.”

(Translated by Matthew Sherry: traduttore@hotmail.com)

————

Sandro Magister is past “vaticanista” of the Italian weekly L’Espresso.

The latest articles in English of his blog Settimo Cielo are on this page.

But the full archive of Settimo Cielo in English, from 2017 to today, is accessible.

As is the complete index of the blog www.chiesa, which preceded it.